Advanced Introduction to Genesis

Introduction

The book of Genesis presents its readers – and hearers – with an understanding of the origins of our world, humankind, and God’s relationship with humanity. The lost paradise and continuous sin and rebellion illustrated humanity’s desperate need for redemption. Even after the flood, the need for understanding, redemption, and a true relationship with God remained evident, with the Tower of Babel highlighting humanity’s misdirection. God’s gracious and loving plan for redemption begins with the dramatic accounts of Abraham and his descendants.

Background

Name

The book of Genesis gained its name from the Greek word génesis, which means “origin,” and highlights the book’s content in its many genealogies and stories of beginnings. The name was obtained from 2:4a of the Septuagint, which reads, “This is the book of the generations/origins (γενέσεως, geneseōs) of heaven and earth.” After the Septuagint used this title to name the book in Greek, the Latin Vulgate then transliterated it to form the word, Genesis. Within Jewish tradition, the book takes its title from its first word, בְּרֵאשִׁית (bereshith).

Author

While the entire Pentateuch is traditionally attributed to Mosaic authorship, it is evident that at least some basic editing occurred, as there are records such as this death (Deut. 34:5). Nonetheless, Mosaic authorship was clearly taught and accepted throughout the entirety of Scripture (cf. Josh 1:7-8; 8:32-35; 22:5; 23:6; 1 Kings 2:3; 2 Kings 14:6; 21:8; 2 Chron. 34:14; Ezra 6:18; Dan 9:11-13; Mal. 4:4; Matt. 19:7-8; Mark 10:3; 12:26; John 1:17; 5:46; 7:19, 23; Acts 3:22; 7:22, 37; Rom. 10:5; etc.).

Hoffmeier rightly venerates Moses as “the liberator and lawgiver of Israel, the most important person in the O.T.” He states that “while Abraham may be regarded as the founder of Israel’s faith, Moses is the founder of Israel’s religion” (p. 415).

Date

The date of Moses’ original works is still debated, but the Exodus is typically thought to have occurred in either the fifteenth or thirteenth century B.C. (Chevalas, 2003; Hoffmeier, 1979-1988). Some scholars have dated the Exodus as early as 1446 B.C., while others place it later, around 1290 B.C. (Youngblood et al., 1995).

Geography

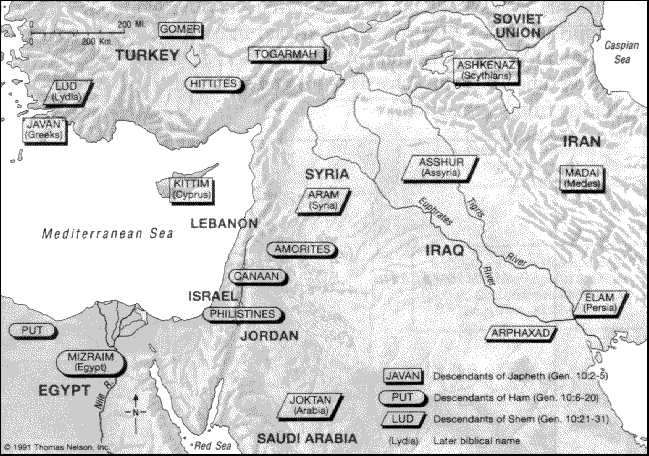

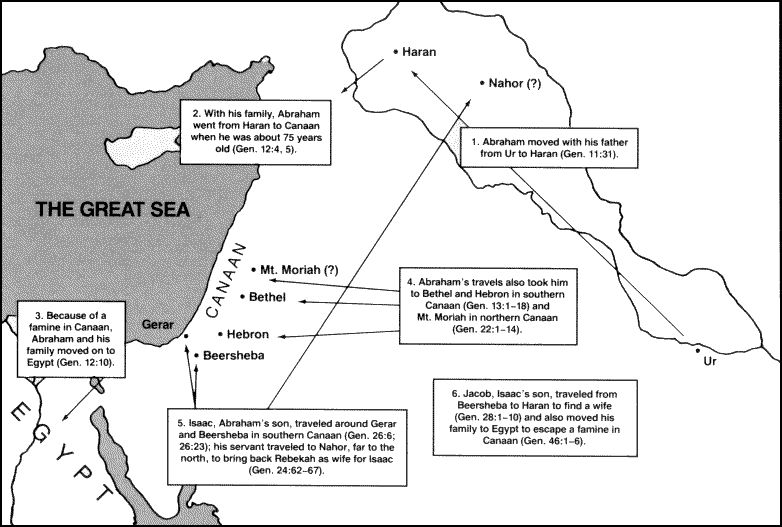

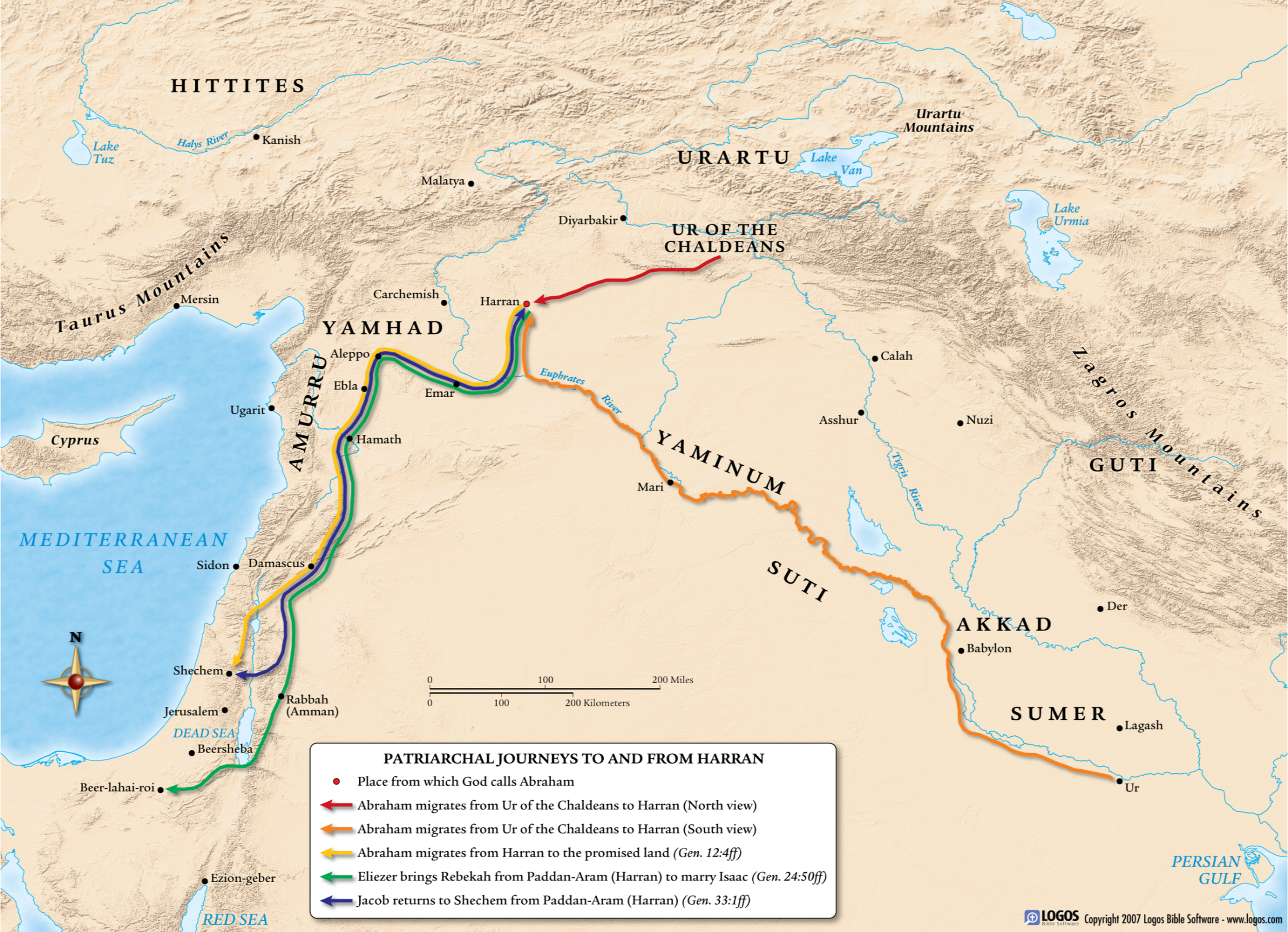

Some initial and helpful maps to introduce the geography and genealogy discussed in Genesis are visible in the following maps from Nelson’s Complete Book of Bible Maps & Charts and Logos Bible Software. The first refers to Genesis 10 and is called the “Table of Nations.” This is structured in terms of the descendants of the three sons of Noah: Japheth (vv. 2–5), Ham (vv. 6–20), and Shem (vv. 21–31). Many names mentioned in chapter 10 are identifiable with nations of ancient times, some of which have continued to the present age. The second refers specifically to the travels of the Patriarchs.

The Nations of Genesis 10

Travels of the Patriarchs

(Further maps will be shared throughout the blogs to assist with visualizing how and where the travels and events occurred.)

Historical Background

Prehistoric Period

When interpreting the passages in the primeval prologue, we must appreciate the inspired author surrounding cultural and literary traditions regarding the origins of the world. Chapter 1, for instance, shows three basic parallels with the creation accounts from Mesopotamia: the picture of the primeval state as a watery chaos, the basic order of creation, and the divine rest at the end of creation. There are also significant similarities between Mesopotamian literature and the primeval prologue regarding the Flood. La Sor et al. (1996) comments,

Beyond basic similarities there are detailed correspondences. The hero is instructed by divine agency to build an unusual boat and caulk it with pitch. He is to take animals along to preserve them from a universal catastrophe. The entire population is destroyed. After the flood waters abate, the hero releases birds to determine if there is any dry land. Eventually the ship comes to rest on a mountain. On leaving the ark, the hero offers sacrifice, and the gods happily smell the sweet odor.6

He further states that,

The clearest connection to Mesopotamia is the account of the Tower of Babel (11:1–9), for it is set in Babylon (v. 2). True to this locale, the building material is mud brick. This setting explains the scornful comment made about this building material (v. 3). The tower is most likely a reference to a ziggurat, a temple constructed as a stepped mountain and made out of clay (v. 4). The name of the city, Babel, reflects the Babylonian name Bâḇili “the Gate of God” (v. 9).

These resemblances prove nothing beyond a genetic relationship between the biblical and Mesopotamian accounts. The Genesis stories in their present form do not go back to the Babylonian traditions. The evidence, even that of the close ties between the Flood stories, merely suggests a diffuse influence of a common cultural heritage. The inspired authors of the primeval account drew on the manner of speaking about origins that was part of a common literary tradition[1] (pp.19-20)

Ancient Near East

La Sor writes,

History in the proper sense began shortly after 3000 in the ancient Near East. A sophisticated culture had already arisen in the great river valleys of both Mesopotamia and Egypt. In Mesopotamia agriculture was advanced, with elaborate drainage and irrigation. Cities were founded and organized into city-states. They cooperated to develop large irrigation projects. These city-states had a complex administrative system. Writing had already been developed. The same was true in Egypt. The numerous local districts in Egypt had formed two large kingdoms, one in the northern delta region and the other in the south. A strong pharaoh then united Egypt but it was always known as the two lands. Hieroglyphic script had already advanced beyond primitive stages. By the Fourth Dynasty (ca. 2600), both administrative structure and technological knowledge enabled the building of the great pyramids at Giza. Furthermore, Egypt and Mesopotamia were already engaged in significant cultural interchange. This took place some 1500 years before Israel was to appear (pp.33-34).

Hinson provides the following concise historical summary,

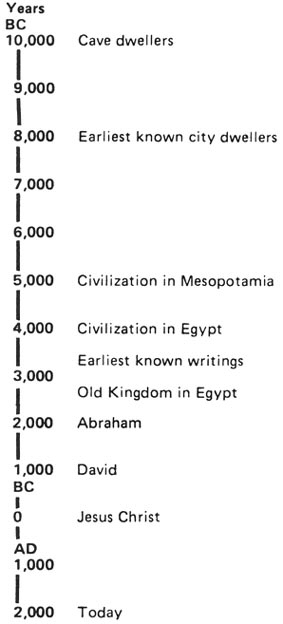

There is evidence of cave-dwellers living in ancient Palestine and South Western Asia as far back as 10,000 b.c. The oldest city whose remains have been uncovered in recent times is Jericho. People first built there about 8000 b.c. The earliest signs that people were living a civilized life in Mesopotamia come from around 5000 b.c., and in Egypt from around 4000 b.c. The earliest known writings come from southern Mesopotamia, and are thought to belong to about 3300 b.c. They were written by a people known as the Sumerians.

For a long time the normal centres of tribal life were single cities, each with its own king who had authority over the neighbouring farm land. The first larger political grouping existed in Egypt about 2900 b.c., and is known as the Old Kingdom. There, three hundred years later, the first Pyramids were built. These are enormous tombs, and it is difficult to realize that they were built at a time when builders had to depend almost entirely upon human strength, since the use of wheels and pulleys had not yet been discovered. The largest of them, known as the Great Pyramid, for example, is 48 feet high, and stands on a square base, with sides 755 feet long. There are 2,300,000 blocks of carved stone in it, each weighing about two and a half tons. The Egyptian kings for whom the Pyramids were built were known as Pharaohs, and were worshipped as ‘God-on-earth’. Their bodies were embalmed and placed in Pyramids to preserve them for their life beyond death. The Egyptians believed that ordinary men and women had no hope of sharing this renewed life beyond the grave.

Time Chart: The place of Israel’s history in the history of humankind

Outline

An elementary outline of the book of Genesis would be:

The Primeval History: Creation, sin, the flood, and the early history of the nations (1:1–11:32)

The Patriarchal Narratives (12:1-36:43)

a) The life of Abraham (12:1–25:18)

b) The lives of Isaac and Jacob (25:19–36:43)

The lives of Joseph and his brothers (37:1–50:26)

A more comprehensive one would be:

Part One: Primeval History (1:1–11:9)

The Creation (1:1–2:25)

a) Creation of the World (1:1–2:3)

b) Creation of Man (2:4–25)The Fall (3:1–5:32)

a) The Fall of Man (3:1–24)

b) After the Fall: Conflicting Family Lines (4:1–5:32)The Judgment of the Flood (6:1–9:29)

a) Causes of the Flood (6:1–5)

b) Judgment of the Flood (6:6–22)

c) The Flood (7:1–8:19)

d) Results of the Flood (8:20–9:17)

e) After the Flood: The Sin of the Godly Line (9:18–29)The Judgment on the Tower of Babel (10:1–11:9)

a) Family Lines After the Flood (10:1–32)

b) Judgment on All the Family Lines (11:1–9)

Part Two: Patriarchal History (11:10–50:26)

The Life of Abraham (11:10–25:18)

a) Introduction of Abram (11:10–32)

b) The Covenant of God with Abram (12:1–25:18)The Life of Isaac (25:19–26:35)

a) The Family of Isaac (25:19–34)

b) The Failure of Isaac (26:1–33)

c) The Failure of Esau (26:34, 35)The Life of Jacob (27:1–36:43)

a)Jacob Gains Esau’s Blessing (27:1–28:9)

b)Jacob’s Life at Haran (28:10–32:32)

c) Jacob’s Return (32:1–33:20)

d) Jacob’s Residence in Canaan (34:1–36:43)

e) The History of Esau (36:1–43)The Life of Joseph (37:1–50:26)

a) The Corruption of Joseph’s Family (37:1–38:30)

b) The Exaltation of Joseph (39:1–41:57)

c) The Salvation of Jacob’s Family (42:1–50:26)

(Nelson’s, 1996)

Note: When you look at outlines in the commentaries, you will find they are much more detailed than the one quoted above. This one has been used because its length is sufficient but not excessive. Also, scholars will not always agree regarding what is the best or most accurate outline. As an example, Archer (1994) presents the following outline,

I. Beginning of Mankind, 1:1–11:32

A. Creation of the world, 1:1–2:3

B. Place of man in the world, 2:4–25

C. Entry of sin and the resultant fall, 3:1–4:26 (Covenant of grace instituted)

D. Antediluvian races and patriarchs (Adam to Noah), 5:1–32

E. Sinfulness of the world purged by the flood, 6:1–9:29

F. Posterity of Noah and the early races of the Near East, 10:1–11:32

II. Life of Abraham, 12:1–25:18

A. Abram’s call, and his acceptance of the covenant by faith, 12:1–14:24

B. Renewal and confirmation of the covenant, 15:1–17:27

C. Deliverance of Lot from Sodom, 18:1–19:38

D. Abraham and Abimelech, 20:1–18

E. Birth and marriage of Isaac, the son of promise. 21:1–24:67

F. Posterity of Abraham, 25:1–18

III. Life of Isaac and his family, 25:19–26:35

A. Birth of Esau and Jacob, 25:19–28

B. Sale of Esau’s birthright to Jacob, 25:29–34

C. Isaac and Abimelech II, 26:1–16

D. Dispute at Beersheba, 26:17–33

E. Esau’s marriages, 26:34–35

IV. Life of Jacob, 27:1–37:1

A. Jacob in his father’s home, 27:1–46

B. Jacob’s exile and journey, 28:1–22

C. Jacob with Laban in Syria, 29:1–33:15

D. Jacob’s return to the promised land, 33:16–35:20

E. Posterity of Jacob and Esau, 35:21–37:1

V. Life of Joseph, 37:2–50:26

A. Joseph’s boyhood, 37:2–36

B. Judah and Tamar, 38:1–30

C. Joseph’s promotion in Egypt, 39:1–41:57

D. Joseph and his brothers, 42:1–45:15

E. Joseph’s reception of Jacob in Egypt, 45:16–47:26

F. Jacob’s last days and final prophecies, 47:27–50:14

G. Joseph’s assurance to his brothers of complete forgiveness, 50:15–26 (pp. 193-194)

Literary Features

Structure

The book of Genesis contains two primary sections: Genesis 1-11 and 12-50. Genesis 1-11 shares the primeval history, with the creation of the world and the stories of Adam and Eve, the Fall, Cain and Abel, Noah’s ark, and the tower of Babel. Genesis 12-50 consists of the ancestral/patriarchal narratives[1], which begin with Abram (who later became Abraham; see Gen. 17:5) and end with the death of Jacob and his son, Joseph.

Genesis 1-11 sets a foundation for the rest of Genesis and the Pentateuch. We now know what the background of the world is for the people of Israel and how they fit into it. We know that God made the world, humanity sinned and continues to sin, the flood happened, humanity recovered, and separate groups and languages were created (11:7-8).

Genesis 12-50 contains valuable Jewish history and serves as a prologue for the book of Exodus. We find in 11:27-32 that Abram and Sarai are an old couple without children. God, however, tells them to leave the land they are in, and He will bless Abram and make him a great nation (12:1-3; cf. 18:18; 28:14). As the book unfolds, we see that with the covenant in chapter 17, God changes Abram’s name to Abraham (v. 5) and Sarai’s name to Sarah (v. 15). Abraham has a son by Hagar (Sarah’s servant) called Ishmael; however, God’s intention was for Sarah to have a child herself, and his name is Isaac.

Isaac later fathers the twins, Esau and Jacob (25:19-36:43). Jacob (God changes Jacob’s name to “Israel”) then has 12 sons, one of whom is Joseph. After being sold by his brothers to traders, Joseph eventually finds himself in Egypt, where he is later elevated to a powerful position in the royal court after interpreting the Pharaoh’s dream. Pharaoh sees God’s spirit and wisdom in Joseph (41:38-39) and hands him his signet ring (41:42). Joseph performs well for Pharaoh and Egypt, and we later see Joseph reunited with his family in Egypt. Unfortunately, however, their people will later be enslaved (37-50; see Exodus).

Throughout Genesis, the characters face many questions and challenges. God instructs and shows love to His people, but poor decision-making – as well as good decision-making – often proves to have its consequences. The themes of God’s promise and blessing are pronounced in Genesis, as God looks to call His people away from a world and ways plagued by sin and into a life and land where they look to Him for instruction and guidance (cf. Deut. 6:1-25).

Are there any Structural Markers?

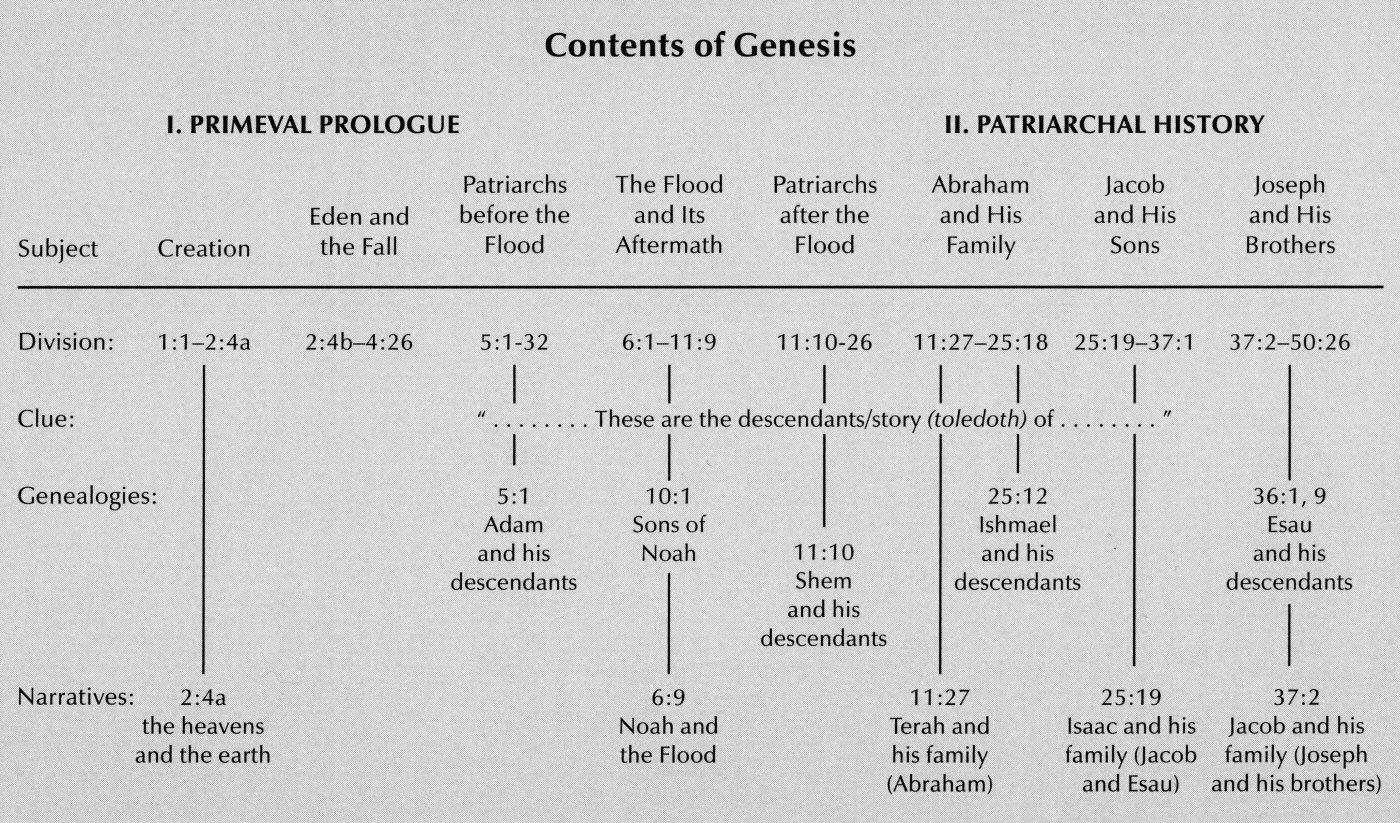

Kissling (2004) interestingly notes that the phrase, “[these are] the generations of” (תוֹלְדוֹת, tôlədôth), is the most obvious structural marker in the book and (with the possible exception of 2:4a) is used as an introductory formula. Generally speaking, there is alternation between narrative material and name list or genealogical material. This yields the following structure for the book:

1:1–2:4 Prologue (Narrative)

2:4–4:26 History of the Heavens and the Earth (Narrative with Genealogy)

5:1–6:8 Family History of Adam (Genealogy)

6:9–9:29 Family History of Noah (Narrative)

10:1–11:9 Family History of Noah’s Sons (Genealogy with Narrative)

11:10–26 Family History of Shem (Genealogy)

11:27–25:11 Family History of Terah (Narrative)

25:12–18 Family History of Ishmael (Genealogy)

25:19–35:29 Family History of Isaac (Narrative)

36:1–37:1 Family History of Esau (Genealogy)

37:2–50:26 Family History of Jacob (Narrative) (p. 30)[2]

The above chart illustrates well how the contents of Genesis fit together (Lasor et al., 1996, p. 17)

Genre

Genesis 1-11

La Sor (1996) states that,

Identifying the genre of Gen. 1–11 is difficult because of its uniqueness. None of these accounts belongs to the genre “myth.” Nor is any of them “history” in the modern sense of eyewitness, objective reporting. Rather, they convey theological truths about events, portrayed in a largely symbolic, pictorial literary style. This is not to say that Gen. 1–11 conveys historical falsehood. That conclusion would follow only if the material claimed to contain objective descriptions. From the above discussion it is certain that such was not the intent. On the other hand, the view that the truths taught in these chapters have no objective basis is mistaken. Fundamental truths are declared: creation of all by God, special divine intervention in the origin of the first man and woman, the unity of the human race, the pristine goodness of the created world, including humanity, the entrance of sin through the disobedience of the first pair, the rampant spread of sin after this initial act of disobedience. These truths are all based on facts. Their certainty implies the reality of the facts.7

Emphasizing solely the similarities to other ancient literature produces a misleading impression that they are the most distinctive features of the material in Genesis. The situation is just the opposite. The reader is first impressed with the unique features of the biblical accounts. Only a trained eye discovers the similarities.

In contrast to the exalted monotheism of Gen. 1–11, the Mesopotamian accounts present gods which are embodiments of natural forces. They know no moral principle. They lie, steal, fornicate, and kill. Moreover, humans enjoy no special dignity in these accounts. They are the lowly servants of the gods, being made to provide them with food and offerings.

The biblical narratives present the true, holy, and omnipotent God. The Creator exists before the creation and is independent of the world. God speaks and the elements come into being. The divine work is good, just, and whole. After the human family rebels, God tempers his judgment with mercy. Even when an account shares common elements with the thought forms of nearby cultures, the distinctive nature of the Creator shines through the narrative.

How then is the unique literary genre of Gen. 1–11 to be understood? One may suppose that the author, inspired by God’s revelation, employed current literary traditions to teach the true theological import of humanity’s primeval history. The book’s purpose was not to provide a biological and geological description of origins. Rather, it was intended to explain the unique nature and dignity of human beings by virtue of their divine origin. They have been made by the Creator in the divine image, yet marred materially by the sin that so soon disfigured God’s good work. (pp. 20-22)

Genesis 12-50

Considering the issue of the literary genre of the Patriarchal narratives, LaSor writes,

Although rediscovery of the ancient world has demonstrated that the patriarchal narratives authentically reflect the period in which the Bible places them, does this mean that they are “history” in the modern sense? Behind all historical writing lie the actual events in space and time. Two major problems interpose themselves between these events and what is called “history.” The first is the problem of knowledge. What are the facts and how have they been preserved? If the historian possesses documentary evidence, what is the interval between the event and when it was recorded? If this interval was spanned by oral tradition, did conditions exist to preserve the facts faithfully, such as a cohesive social group with historical continuity? Much will depend upon how historians come to know about the events they record.

The second problem is significance. To record all that happened is impossible. Furthermore, many events are insignificant for particular purposes. To the political historian a marriage contract between common people is of little interest, whereas to the social historian it is primary. History writing is much more than the bare chronicling of events. It involves a selecting of events, relating them to one another, and determining cause and effect. Therefore, the question of the writers’ purposes, on the basis of which they select their data, becomes of paramount importance.

The biblical writers were not exempt from either of these considerations. Their writing under divine inspiration (see below, ch. 45) does not imply anything different about their human, material knowledge of the past. Inspiration did not give them new information or make the obscure clear. They frequently mention sources (Num. 21:14; Josh. 10:12f.; 1 Kgs. 14:19). A comparison of passages reveals vast differences in their knowledge of the past.

The aims of the biblical authors are largely theological, so they select events and incidents in keeping with their primary interest in God’s actions in bringing about his purpose. They recount what God has done to inspire faith. They do not falsify history, but they are highly selective in light of their purposes. This is especially true in Genesis, in which several centuries are covered.50

In this light, what can be said about the historical genre of the patriarchal narratives? First, they are family history, handed down primarily through oral tradition. Pastoral nomads normally do not keep written records. There is little interest in relating their story to contemporary events. The narratives are grouped in three “cycles” (stemming from three of the patriarchal generations), marked off by the toledoth formula. They give only the most general indications of chronological relationship. If the chronology is pressed, difficult problems result. For instance, in Gen. 21:14 Abraham is said to have placed Ishmael on Hagar’s shoulder and sent her off into the desert. Based on the chronology of the sequence of chapters, Ishmael was 16 years old (16:16; 21:5). Again, Jacob was born when Isaac was 60 (25:26), and Isaac died at 180 (35:28). A similar reading finds that Rebekah was deeply disturbed about a wife for Jacob (27:46) when he is between 80 and 100 years old!

Some traditions are difficult to harmonize with history. Both Midian and Ishmael are Joseph’s great-uncles, yet the Midianites and Ishmaelites appear in his boyhood as caravan merchants plying their trade between Transjordan and Egypt (37:26–28). Amalek is the grandson of Esau (36:12), Abraham’s grandson, yet in Abraham’s day the Amalekites were settled in southern Palestine (14:7).

These facts are problematic only if these cycles are interpreted as history in a modern sense. Their primary purpose is to show the unfolding of Abraham’s call. With that call God makes definitive promises to Abraham (12:1–3). The succeeding chapters show how God brought these promises to pass in spite of Abraham’s lack of an heir (see below, p. 47). This kind of “history writing” must be recognized as the “remembered past”—the folk memory of a people. The distinction between this style and that of the historical writing in the time of Israel’s monarchy is not in the historical reality of the events but in the manner of their presentation. The centuries have been bridged by oral tradition.51 In primitive societies, oral tradition is far more precise than can be imagined by the modern western reader.52 The patriarchal culture provided an ideal environment for the accurate transmission of tradition: it was characterized by a closed social sphere bound by ties of blood and religion. These narratives, then, are vital traditions which were kept alive by the collective memory of the tribe. (pp.43-45)

Theology

The theology of Genesis is a huge subject, and as Wenham (1987) states, simply dealing with the theology of chapters 1-11 would “require a book of its own” (p. xlv). Nonetheless, there are several valuable theological themes and insights throughout Genesis that help us to better understand God, man, and Scripture.

Theology of Genesis 1-11

Below are some of the qualities of God revealed in the book of Genesis:

Genesis confronts us with the Living God, who is unmistakably personal.

He is the only God, the Creator and Sovereign of all that is.

His ways are perfect.

He is self-revealed.

God’s unity is not monolithic (in the terms ‘the Angel of the Lord’ or ‘of God’[2] and ‘the Spirit of God’,[3]).

He is omnipotent and omniscient

He is caring.

He is a God of goodness.

Chapters 1-11 show two opposite progressions: God’s orderly creation and the disintegrating work of sin. The climax of God’s orderly creation was the creation of man (i.e. humanity) as a responsible and blessed being. The disintegrating result of sin shows its first great anticlimax in the corrupt world of the flood and its second in the folly of Babel (Kidner, 1967, p. 16).

An interesting point is the originality of the concept of an all-powerful creator speaking the world into existence without a hint of resistance by the creation. Kissling (2004) states, “This point which seems so obvious to us was strikingly original in the ancient world where the forces of what we call nature were actually manifestations of various gods who were in tension with each other” (p. 26). The following words from Gordon Wenham (1987) regarding the interpretation of Genesis 1-11 are also valuable:

If it is correct to view Gen 1–11 as an inspired retelling of ancient oriental traditions about the origins of the world with a view to presenting the nature of the true God as one, omnipotent, omniscient, and good, as opposed to the fallible, capricious, weak deities who populated the rest of the ancient world; if further it is concerned to show that humanity is central in the divine plan, not an afterthought; if finally it wants to show that man’s plight is the product of his own disobedience and indeed is bound to worsen without divine intervention, Gen 1–11 is setting out a picture of the world that is at odds both with the polytheistic optimism of ancient Mesopotamia and the humanistic secularism of the modern world.

Genesis is thus a fundamental challenge to the ideologies of civilized men and women, past and present, who like to suppose their own efforts will ultimately suffice to save them. Gen 1–11 declares that mankind is without hope if individuals are without God. Human society will disintegrate where divine law is not respected and divine mercy not implored. Yet Genesis, so pessimistic about mankind without God, is fundamentally optimistic, precisely because God created men and women in his own image and disclosed his ideal for humanity at the beginning of time. And through Noah’s obedience and his sacrifice mankind’s future was secured. And in the promise to the patriarchs the ultimate fulfillment of the creator’s ideals for humanity is guaranteed.

These then are the overriding concerns of Genesis. It is important to bear them in mind in studying its details. Though historical and scientific questions may be uppermost in our minds as we approach the text, it is doubtful whether they were in the writer’s mind, and we should therefore be cautious about looking for answers to questions he was not concerned with. Genesis is primarily about God’s character and his purposes for sinful mankind. Let us beware of allowing our interests to divert us from the central thrust of the book, so that we miss what the Lord, our creator and redeemer, is saying to us. (p. liii)[5]

Theology of 12-50

Understanding the greatness of God’s creation, and the power of sin, a plan is necessary to overcome evil that is now destroying creation; God’s universal blessing at creation (1:26-28) is not retracted. The way God chooses to do this begins with one family, the family of Abraham. It is an intriguing point, however, that Genesis’ dominant message about the elect family of Abraham is actually how flawed they are! Furthering this point is the surprising presentation of many outside of the chosen line. For instance, Ishmael and Esau are not chosen but are still blessed. Melchizedek is a priest of God Most High but has no direct connection to the chosen family. While Abimelech is a pagan king, he is still concerned about righteousness. Tamar, a Canaanite, is acknowledged by Judah as being more righteous than himself, and the Pharaoh in Joseph’s time is accepting of God’s revelation that Joseph interprets for him. Obviously, there are examples of those outside the chosen family (e.g. Sodom and Gomorrah) who are unrighteous in their beliefs and behaviour.

Hamilton (1990) presents a compelling question we should consider: why are those doing the wrong thing winning? He insightfully states,

If Gen. 12–50 is punctuated with stories highlighting unconscionable behavior in the lives of the major actors, so is Exod. 1–31. Why, for instance, does God give his people manna in the desert when they murmur and complain (Exod. 16)? God answers prayer; does he answer grumbling too? Why, then, when they grumble about food a second time (Num. 11), does God send them food, but “while the meat was still between their teeth … he struck them with a severe plague” (Num. 11:33)? Both Exod. 16 and Num. 11 describe the same kind of sin, but in Exod. 16 there are no consequences, while in Num. 11 there are grave consequences. Would Exod. 16 and Num. 11 lead us to the conclusion that the God of Israel is inconsistent and unpredictable? Of course, the difference between Exod. 16 and Num. 11 is that Exod. 16 is about a pre-Sinaitic, pre-covenant sin, and Num. 11 is about a post-Sinaitic, post-covenant sin. The signing and acceptance of a covenant of God makes all the difference in the world. The greater the privileges, the greater the responsiblities. This principle may be illustrated in the different penalties attached to fornication (Exod. 22:16–17), a premarital sexual sin, and adultery (Deut. 22:22), a postmarital sexual sin. In the latter the penalty is death; in the former the penalty is a fine on the man, and marriage with the virgin he seduced if her father approves.

In the light of the divine silence, earlier commentators on Genesis have tried to sidestep the moral, ethical issues or even justify the patriarchs, when those patriarchs were involved in scandalous behavior. Many of the church fathers avoided the problem, primarily by opting for an allegorical reading over against a literal reading of the biblical text. Early Jewish exegesis similarly sidestepped the issue by embellishing the Genesis stories with folklore and legend. Thus, Abraham did not betray Sarah, but rather concealed her in a box.87 The Reformers, such as Luther and Calvin, argued that the patriarchs were given, albeit temporarily, a special dispensation to break the moral law.88 For the last four centuries attempts have been made either to exonerate the patriarchs or to dismiss them as curmudgeons of a primitive morality.

Either of these approaches misses the focus of Gen. 12–50. Genesis is not interested in parading Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob as examples of morality. Therefore, it does not moralize on them. What Gen. 12–50 is doing is bringing together the promises of God to the patriarchs and the faithfulness of God in keeping those promises. Even if the bearers of those promises represent the greatest threat to the promises, the individual lives of the promise bearers cannot abort those promises. Whenever they find themselves in a delicate situation (in Egypt, in prison, with another not one’s spouse, running from one’s brother, in famine), God saves his elected own from destruction. God will no more scrap this chosen family, their moral inadequacies notwithstanding, as an object of his blessing and as the light and salt of the earth’s nations, than he would scrap the new covenant equivalent of this family, that is, the church (Gk. ekklēsía, “the called”).

So then, Gen. 12–50 is to be read as an illustration of God’s faithfulness to his promises. These same chapters may not be read as justifying sinful behavior in God’s children, as if that is one of their major theological contributions. “To be human is to be sinful (even after redemption)” is a dictum neither of Gen. 12–50 nor of the rest of Scripture. Rather, it borders on a gnostic fallacy that would equate our created humanity with sinfulness. (pp. 45-47)

To finish this basic section on Genesis theology, I wanted to share the words of both Paul Kissling and former Professor and dear friend, Thomas H. Olbricht. Kissling summarises the biblical context of Genesis, writing,

Genesis 11:27–50:26 is the continuation of Genesis 1:1–11:26. The book of Genesis is part of the Pentateuch. The Pentateuch is part of the Old Testament. The Old Testament is the first three quarters of the Christian Bible. These simple facts must always be kept in mind when interpreting Genesis 11:27–50:26. The relationship between this section of Genesis and the rest of the Bible is a theological one, but it is theology expressed in narrative. Genesis 11:27–50:26 is a crucial link in the Bible’s micronarrative. (p. 31)

Olbricht, emphasising the loving nature of God in his OT theology, shares the following refreshing message of hope and God’s grace regarding the story of Joseph,

This distribution of the good gifts of the earth becomes a paradigm out of which Israel understands her function on earth. She mans the warehouse from which the good gifts of God are distributed to the whole earth.

No doubt there were periods along the way when Joseph wondered how anything of significance could turn up. He went from bad to worse, from his father’s house to slavery, to prison. But finally a turn-around occurred, and when it did, he ended up controlling the food supplies for the whole earth. Joseph could see the involvement of the Lord (Gen. 50:20-21)

The Lord had in mind all the time that Joseph would be his servant through whom he would bless the nations. So we too, not knowing the outcome of our life’s work, stand by faith knowing that when our life is over we can discern how God has worked through us to bless the peoples who inhabit this globe. ()

Conclusion

The book of Genesis sets an invaluable platform for the Pentateuch and beginning of the Old Testament and biblical story. For many reasons, there is an enormous amount of information and theology in the study of Genesis, and if you got to the end of this post, I hope it has been enlightening and of good use to you.

Reflective Thoughts to Consider

What is the motivation behind your life story? How are you going to contribute to the storyline of humanity?

Where do you fit in the story? Do you empathise with any particular biblical characters?

What do you learn about God in His actions throughout Genesis?

What connections are there between Jesus and the book of Genesis?

Who or what do you find inspirational in the stories of Genesis?

If you were some of the characters, what would you have done differently, and why? In reflection, try empathising and slipping into their place in history and culture. Would your initial answers to the questions remain the same?

How are the theological themes relevant to yourself and those around you?

How do the worldviews of those today differ from each other? Are there any connections between how people in different countries today see things, and how people in different times see things? Do you think different cultures (and even tribes) – and the same cultures at different times – had different ways of seeing things?

There is often an arrogance among atheists today that humanity is closer to truth today than they ever have been, and it is no thanks to Christianity. Can you see any correlations here to the Tower of Babel?

Bibliography

Alexander, T. D. (2003). Authorship of the Pentateuch. In W. D. Baker (Ed.), Dictionary of the Old Testament: Pentateuch. InterVarsity Press.

Anderson, J. E. (2016). Genesis, Book of. In J. D. Barry, D. Bomar, D. R. Brown, R. Klippenstein, D. Mangum, C. Sinclair Wolcott, L. Wentz, E. Ritzema, & W. Widder (Eds.), The Lexham Bible Dictionary. Lexham Press.

Archer, G., Jr. (1994). A survey of Old Testament introduction. (3rd. ed.). Moody Press.

Baker, D. W. (2022). The Table of Nations: an ethno-geographic analysis (Gen 10:1–32). In B. J. Beitzel (Ed.), Lexham Geographic Commentary on the Pentateuch. Lexham Press.

Barry, J. D., Mangum, D., Brown, D. R., Heiser, M. S., Custis, M., Ritzema, E., Whitehead, M. M., Grigoni, M. R., & Bomar, D. (2012, 2016). Faithlife study Bible. Lexham Press.

Beitzel, B. J., ed. (2022). Lexham geographic commentary on the Pentateuch. Lexham Press.

Brannan, R., Penner, K. M., Loken, I., Aubrey, M., & Hoogendyk, I., eds. (2012). The Lexham English Septuagint. Lexham Press.

Chavalas, M. W. (2003). Moses. In T. D. Alexander & D. W. Baker (Eds.), Dictionary of the Old Testament: Pentateuch (pp. 570-579). InterVarsity Press.

Hamilton, V. P. (1990). The Book of Genesis, Chapters 1-17. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co.

Hinson, D. F. (1990). History of Israel (Vol. 7). S.P.C.K.

Hoffmeier, J. K. (1979–1988). Moses. In G. W. Bromiley (Ed.), The International Standard Bible Encyclopedia, Revised (Vol. 3, pp. 415-425). Wm. B. Eerdmans.

Jacobsen, T. (1981). The Eridu Genesis. Journal of Biblical Literature, 100. 511-529

Kidner, D. (1967). Genesis: An introduction and commentary. Vol. 1). InterVarsity Press.

Kissling, P. J. (2004–). Genesis (Vol. 1). College Press Pub. Co.

Kissling, P. J. (2009). Genesis (Vol. 2). College Press Pub. Co.

Kittel, G., Friedrich, G., & Bromiley, G. W. (1985). Génesis. In Theological Dictionary of the New Testament, abridged in one volume (pp. 117-119). W.B. Eerdmans.

La Sor, W. S., Hubbard, D. A., & Bush, F. W. (1996). Old Testament survey: the message, form, and background of the Old Testament. William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company.

Longman, T., III. (2005). How to read Genesis. IVP Academic.

Nelson’s complete book of Bible maps & charts: Old and New Testaments (Rev. and updated ed.). (1996). Thomas Nelson.

Olbricht, T. H. (1980). He loves forever: the message of the Old Testament. Journey Books

Turner, L. A. (2003). Genesis, Book of. In T. D. Alexander & D. W. Baker (Eds.), Dictionary of the Old Testament: Pentateuch. InterVarsity Press.

Wenham, G. J. (1987). Genesis 1–15 (Vol. 1). Word, Incorporated.

Youngblood, R. F., Bruce, F. F., & Harrison, R. K., eds. (1995). “Exodus, the”. In Nelson’s new illustrated Bible dictionary. Thomas Nelson, Inc.; Logos Bible Software.

Footnotes

6 For a detailed study of these similarities, see Heidel, Gilgamesh Epic and Old Testament Parallels, 2nd ed. (Chicago: 1949), pp. 244–260.

[1] “Patriarchs” (“fathers”) is the name given to Abraham, his son Isaac, and his grandson Jacob—the major characters in Genesis 12-50.

7 Cf. B. S. Childs, Introduction to the Old Testament as Scripture (Philadelphia: 1979), p. 158. “The Genesis material is unique because of an understanding of reality which has subordinated common mythopoeic tradition to a theology of absolute divine sovereignty.… Regardless of terminology—whether myth, history, or saga—the canonical shape of Genesis serves the community of faith and practice as a truthful witness to God’s activity on its behalf in creation and blessing, judgment and forgiveness, redemption and promise.”

50 To others with differing purposes, it may seem at times as if they have distorted their accounts, but this is a matter of viewpoint. See further J. R. Porter, “Old Testament Historiography,” pp. 125ff. in G. W. Anderson, ed., Tradition and Interpretation (Oxford: 1979).

51 There seems to be nothing against the hypothesis that these traditions were first put into writing in Moses’ time (and likely at his instigation). In view of the fact that various contracts, particularly marriage contracts, are of great antiquity, it is not unreasonable to suppose some written documents. Further, the widespread use of patronymics (Abram ben Terah, etc.) makes the recording of genealogical lists relatively easy.

52 On the tenacity of oral tradition, see Albright, From the Stone Age to Christianity, pp. 64–76, esp. 72ff. For a less positive evaluation of oral tradition, see R. N. Whybray, The Making of the Pentateuch: A Methodological Study (Sheffield: 1987), pp. 138–185.

87 The example is taken from B. S. Childs, Old Testament Theology in a Canonical Context (Philadelphia: Fortress, 1985), p. 213.

88 See R. Bainton, “The Immoralities of the Patriarchs according to the Exegesis of the Late Middle Ages and the Reformers,” HTR 23 (1930) 39–49.

[2] Cf. 16:7–11, with verse 13; 18:1, with verses 2, 33 and with 19:1; 31:11, with verse 13; 32:24, 30, with Hos. 12:3–6; 48:15, with verse 16.

[3] 1:2; cf. 6:3; 41:38.